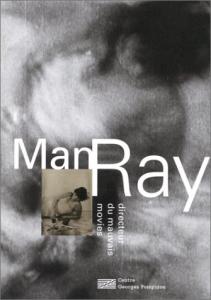

Director of bad movies" was the title that Man Ray gave himself at the bottom of a letter sent on June 8, 1921 to Tristan Tzara, a letter reproduced at the beginning of the work, which the artist had decorated with a piece of film showing her face, and another fragment on the frontispiece presenting a female nude.

Place in the archives therefore, in this booklet which benefits from the contribution of the Man Ray and Noailles donation to the Center Georges Pompidou, and which the two directors, specialists of experimental cinema, have perfectly managed to present us behind the scenes of the work of the American author.

Because if there is no shortage of works on Man Ray as a photographer, the cinematographic production of the Dadaist and then surrealist artist remains too often poorly known. The film, it is true, does not lend itself well to publication, but this work attempts by diversifying the iconography (photograms, manuscripts, etc.), by playing with reproductions of film strips, to offer the reader a tool for analysis which extends the projection.

In the first part, Patrick de Haas draws up a first aesthetic typology of Man Ray's films, showing how, from cine-rayograms such Return to Reason (1923), based on the notion of automatism, the artist then developed the principle of improvisation with Parisian wanderings with camera in hand (Emak Bakia, 1926), then came to more specifically surrealist films. , where meaning bursts into poetic metaphors (L'Étoile de mer, 1928) to culminate in the romantic dream of the total work of art, on the occasion of the luminous ballets Organs commissioned by Paul Poiret during the Arts Exhibition decorative from 1925.

Each film is then analyzed, unpublished documents, film scraps, script sketches and an anthology of texts form all documents allowing us to reconstruct the genesis of the films and to measure their historical and aesthetic significance.